- When examining products, why do importers only inspect a sample?

- Importers must accept their goods will never be 100% defect-free – but where to set their acceptable limit for quality?

- Acceptance Quality Limit (AQL) tables set the theoretical limits for quality, but the final say on whether to accept goods comes from the brand.

AQL: An Acceptance Quality Limit is a test and/or inspection standard that prescribes the range of the number of defective components that is considered acceptable when random sampling those components during an inspection.

It is more than likely that you’ve encountered products that have stopped working much sooner than you would reasonably expect. Scissors that lose their sharpness after a few weeks, dried-up envelopes that no longer stick down or shoelaces that snap the third time you tie them. These defects may be annoying, but incidents like these would be even more common if it weren’t for the work of quality inspection services.

The most popular inspection method used today is acceptance sampling. It revolves around testing a randomly picked sample batch of a given product and using statistics to assume the quality of the entire production run. The method’s popularity is down to the fact that the inspection results produced are easy to interpret. Furthermore, it is time and cost effective, because it take fewer personnel a shorter amount of time to complete.

Acceptance Quality Limit (AQL)

It Started With a Bang!

Whilst acceptance sampling is now an important method of statistical quality control, it was not widely followed prior to the mid-1900s. It was popularized by mathematics professors H.F. Dodge and H. Romig and originally used by the U.S. military to test the quality of bullets during World War II.

You’re Never Going to be 100% Defect-free

There will be defective products in virtually every production batch. In many supplier/buyer relationships, the supplier is not expected to deliver defect-free goods. In fact, what the buyer wants is not to have too many defects, in order to control the quality of purchased goods. But what does “too many” mean? This is where AQL tables come in.

The Most Essential Tool

Acceptance Quality Limit (AQL) tables are the most indispensable, industry-standard, statistical tool at the disposal of international product inspectors and manufacturers. They are defined as the limit a buyer sets regarding the “quality level that is the worst tolerable”.

In other words, the table’s key function is to communicate the maximum number of defective units allowed in a lot, beyond which a batch is rejected, thus providing a standard by which to judge the quality of each lot. These statistical tables help determine two key elements:

- How many samples from a batch of products should be selected and inspected?

- When it comes to defective products, where is the limit between acceptability and rejection?

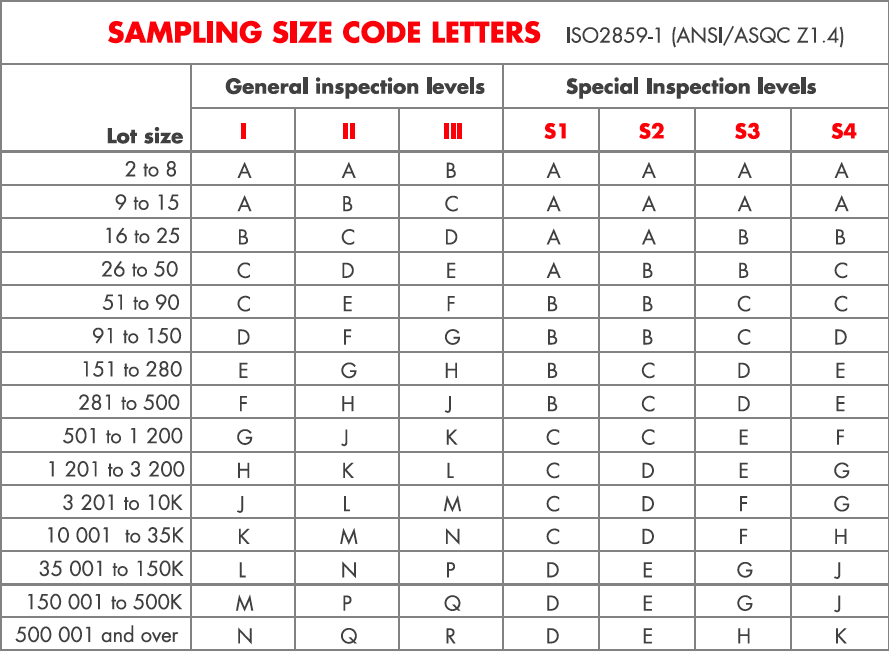

AQL tables actually consist of two separate tables – the first one features the ‘lot size’ (number of ordered products) and the corresponding ‘general inspection level’ code letter:Once you know which code letter to use, the second table will provide you with the inspection sample size, as well as the maximum number of defects within that sample that can be accepted.

Before using the AQL tables, importers should be aware of the following three parameters:

- The lot size – The number of items ordered is the lot size, and it is advised to perform separate inspections for each lot. If only one product was ordered, the lot size is the total batch quantity.

- The inspection level – Three inspection levels dictate how many samples to inspect:

- Level I – This is the least strict inspection level. It can be used if the importer has a lower tolerance for product quality issues, such as with lesser-value gifts that come free with a purchase. Or perhaps a supplier has passed all previous inspections, and the buyer feels confident in their product quality. It is important to understand that settling for a Level I inspection as a way to spend less time and money is a high risk strategy.

- Level II – Used by default, Level II is the most widely adopted.

- Level III – The most strict inspection level, Level III dictates the largest sample size and is, therefore, most representative of the overall quality of the products. Buyers may opt for a Level III inspection for high-value products (example: luxury goods).

- The AQL level appropriate for your market – AQLs are highly flexible because they allow importers to customize the quality tolerance for their product. Importers usually set different AQLs for critical, major, and minor defects.. Although standardized AQLs of 0% for critical defects, 2.5% for major defects, and 4% for minor defects are often used, a buyer might require stricter AQLs for high-value items or markets with higher consumer expectations.

When the buyer specifies these particular AQLs, it is an indication that as long as the percentage of defective items in the lots supplied by a manufacturer is lower than the AQL, most of the shipment will be accepted.

Let’s look at an example

Let’s say you are the importer of smartphone cables. For most consumer goods, the limits fixed by the buyer for the three types of defects are:

- 0% for critical defects (totally unacceptable: a user might get harmed, or regulations are not respected) – e.g. the smartphone cables overheat and melt.

- 2.5% for major defects (these products would usually not be considered acceptable by the end user) – e.g. there are highly visible cracks in the smartphone cable casing.

- 4.0% for minor defects (there is some departure from specifications, but most users would not mind) – e.g. the color of the smartphone cables are slightly different than expected.

Now we know what our acceptable limits are for the shipment of smartphone cables in this example, we can follow at a step-by-step guide for using the AQL tables:

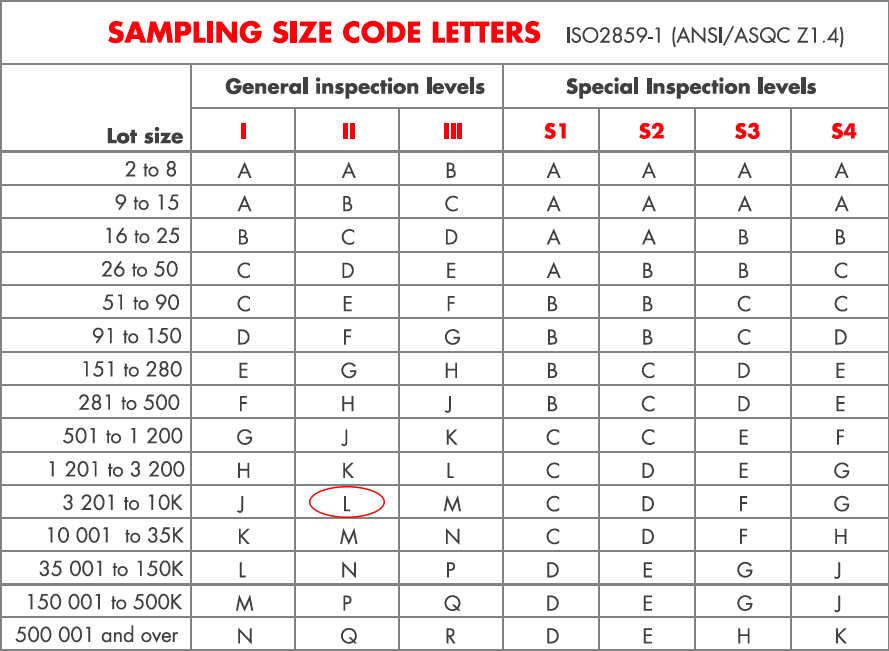

- We are supposing that the lot size for this batch of smartphone cables is 5000.

- Using the AQL table, we can see that for a lot size of 5000, the corresponding letter code for the default inspection level of ‘II’ is ‘L’.

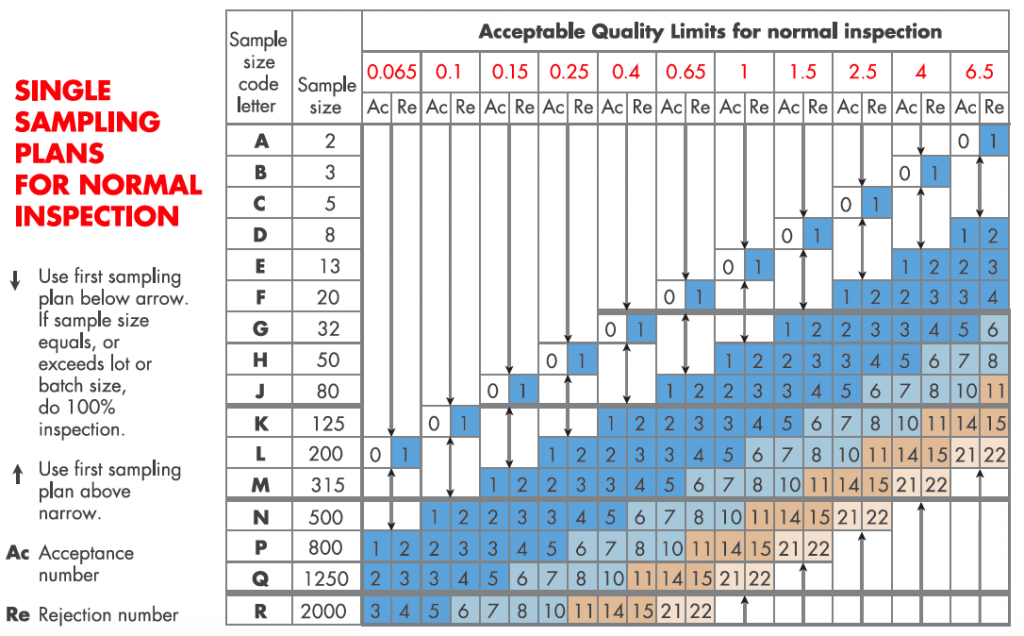

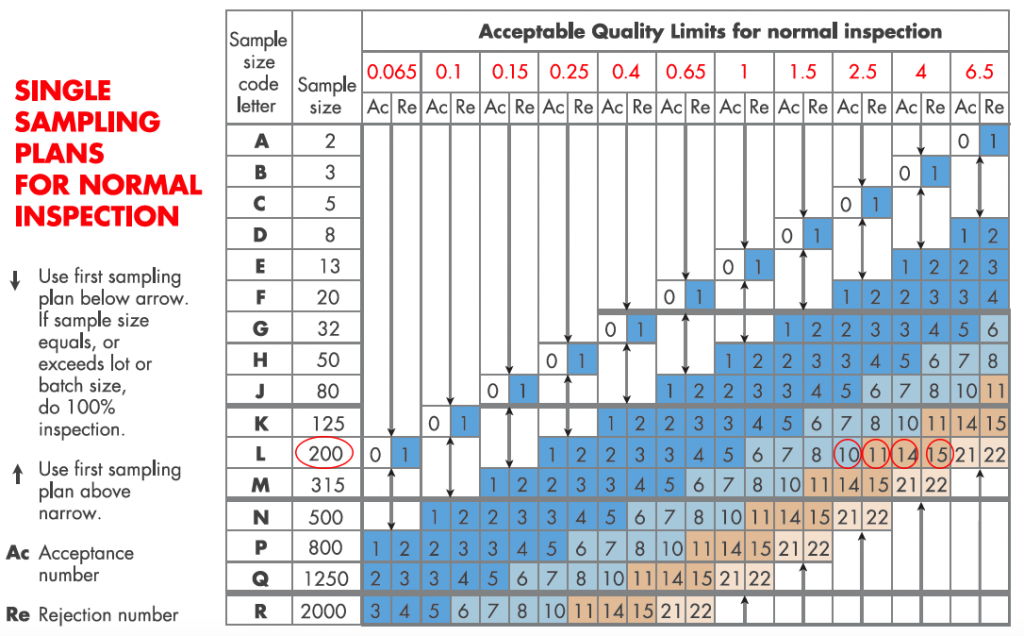

- Next, using the code L, we can see that the sample size for inspection is 200 pieces.

- We now need to pull a random selection of 200 sample pieces for inspection, taken from across the total production run of 5000 smartphone cables.

The next step for the buyer is to determine how many defects to allow in the AQL sample:

- Critical – 0% is a typical limit for critical defects, so finding any critical problems in the sample size means the entire production run will fail.

- Major – On the AQL chart, we find our sample size of 200 pieces. At the top, we find the AQL of 2.5. Where the row and columns meet there are two numbers: (Ac) 10 and (Re) 11.

This shows us that the maximum acceptable (Ac) number of defects in this sample size is 10, while the minimum number of defects that will result in a rejection (Re) of this sample is 11.

- Minor – The same process is repeated, but this time, at the top of the AQL chart we find the AQL of 4.0. Again, where the row and columns meet, the two numbers are (Ac) 14 and (Re) 15.

This time, the maximum acceptable (Ac) number of defects in this sample size is 14 and the minimum number of defects for rejection (Re) of this sample is 15.

In other words, the goods are accepted if no critical defect, no more than 10 major defects or no more than 14 minor defects are found.

E.g., if 16 major defects and 13 minor defects are discovered, the goods will be refused because the number of major defects is higher than the defined acceptance quality limit (even though the number of minor defects found was smaller than the limit). However, if 8 major defects and 9 minor defects are detected, the product run will be accepted.

Importers Have the Final Word

The importer has the task of interpreting the results of an inspection, they typically have the final say on whether to accept an order of goods from the manufacturer.

In some cases, an inspection report might state that an order failed an inspection, but the importer could decide that the inspection criteria was too strict and agree to accept the shipment of goods anyway – or vice versa – they may decide that a passed inspection was too lenient, and refuse to accept the products. It all depends on the individual importer’s appetite for risk and their tolerance for quality issues.